Circumcision indecision: The ongoing saga of the world’s most popular surgery

Imagine you were given the task of concocting a controversial topic from scratch. You would probably throw in some religion, add a dash of politics and, to really spice things up, include a heaping portion of sex. To help generate heated debate, you could also sprinkle a few human rights issues on it. Next stir in a whole pot of health claims — some sound, some spurious (just to keep things interesting). Oh, and it couldn’t hurt to somehow work helpless babies into the mix to get parents all riled up.

Well, you don’t need to create that topic. It already exists. It’s called circumcision. And just because it is the most commonly performed surgical procedure in human history doesn’t mean people have reached a consensus on the health benefits of slicing off foreskins. Far from it.

About a third of the world’s males aged 15 years and older are circumcised, according to the World Health Organisation. Most undergo the procedure for religious reasons: 68.8% of the world’s circumcised men are Muslim, with an additional 0.8% belonging to the Jewish faith. Among those not belonging to the Muslim or Jewish religions, 12.8% of circumcised men hail from the United States, with the remaining 17.6% spread throughout the rest of the world.

In recent history, most developed nations have largely abandoned the practice. Circumcision rates started to fall rapidly in the United Kingdom in the 1950s, in New Zealand in the 1960s and in Canada in the 1990s. In many European countries, nonreligious circumcision is almost unheard of.

Even in the United States — the outlier of the Western world, where nearly 80% of men are circumcised — more parents are choosing to leave their newborn boys intact. According to recent statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of newborn circumcision has been falling for a decade and now lies somewhere in the 56%–59% range. Still, the circumcision of newborns “is so common that most parents and physicians scarcely think of it as surgery,” medical historian David Gollaher wrote in his book on the practice (Gollaher D. Circumcision: A History of the World’s most Controversial Surgery. New York (NY): Basic Books; 2000. p. xii).

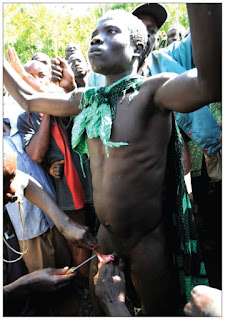

So how did this procedure become so popular in the first place? Much of that can be attributed to religion, of course, but also to ethnic traditions. That’s why the circumcision rate is so high in some African nations, such as Ethiopia (92%), yet remains low in other parts of the continent, such as Uganda (14%). The lower rates are on the rise now, however, following a series of African clinical trials that suggest circumcision can lower HIV transmission rates in heterosexual men by up to 60%.

It wasn’t until the mid-19th century, though, that circumcision gained popularity in the medical community. In Britain, it was seen as a means to promote chastity and deter masturbation, which at the time was seen as a pathological practice that led to all sorts of harm, including blindness and mental illness. The Victorian-era abhorrence of many forms of sexual activity even led to the creation of a disease: “spermatorrhoea.” A man could acquire this ailment by emitting semen outside of marital intercourse.

“The deepest origins of routine circumcision lie in the extraordinary mental gymnastics by which normal male sexuality — the production and emission of sperm — was categorized as a life-threatening disease,” Australian historian Robert Darby wrote on his website detailing the history of circumcision. “Circumcision is a culturally determined practice which, in the Anglophone world, acquired a thick veneer of medical rationalization,” he added.

The rise of circumcision in the US can be attributed, in part, to the work and writings of Dr. Lewis Sayre, an orthopedic surgeon, in the late 1800s. He claimed to have healed one patient from paralysis of the legs by removing an excessively tight foreskin, and later went on to promote circumcision as a cure for other boyhood ailments.

“I am quite satisfied from recent experience that many of the cases of irritable children, with restless sleep, and bad digestion, which is often attributed to worms, is solely due to the irritation of the nervous system caused by an adherent or constricted prepuce,” wrote Sayre (American Medical Association. Transactions of the American Medical Association. 1870;21:205–11).

Since that time, doctors have embraced circumcision for many reasons, citing research that suggests it can reduce rates of sexually transmitted diseases, penile cancer, urinary tract infections and slow the transmission of HIV. Though these claims are based on data rather than anecdotes, modern medical debates on the health benefits of circumcision can still turn into a game of “my science is better than your science.”

Australian emergency physician Dr. David Cooper and colleagues once referred to the procedure as a “surgical vaccine” and called for a boost in infant circumcision rates to reduce the transmission of HIV (Med J Aust 2010; 193:318–9). A slew of letters ensued in response to the editorial, with supporters and naysayers accusing each other of citing “inconclusive, low-quality evidence” and “superseded and spurious references” and “an outlier study” and clinical trials with “serious methodological flaws” and so on and so on (Med J Aust 2011;194:97–101).

Then there are the debates regarding the value of the foreskin. Advocates of circumcision say it may have served to protect the glans of the penis from external threats (thorns, cold, insects) back in the days when men ran around naked, but it has been made obsolete by boxers and briefs and pants. Opponents counter with arguments that the foreskin is loaded with nerve endings and is vital for sexual sensitivity. In turn, circumcision advocates counter that if circumcised penises were any more sensitive they would cry at weddings.

In short, circumcision is a contentious topic, both in the medical community and the public. Some think of it as the status quo, some don’t think about it at all, some think it can vastly improve health, some think it violates an infant’s basic human rights and some think it connects them with God.

Comments

Post a Comment